This post includes four different entries, as I have to make up the three that I missed and complete the one due on Sunday.

Due Sunday, Mar. 8

Delbaere, M., McQuarrie, E.F., & Phillips, B.J. (2011). Personification in Advertising: Using a Visual Metaphor to Trigger Anthropomorphism. Journal of Advertising, 40, 121-130.

Personification “taps into the deeply embedded human cognitive bias referred to as anthropomorphism — the tendency to attribute human qualities to things” (121). This article, which focuses on visual images in print advertising, posits that personification can encourage people to anthropomorphize things. Advertising sees positive results when subtle visual changes make static print ads appear to be engaged in some sort of human behavior. Personification is typically understood as a figure of speech that gives human qualities to inanimate objects. However, rhetorical personification invokes anthropomorphism as well as metaphorical processing. We’ve seen anthropomorphism in advertising with spokescharacters (e.g., the Geico gecko, M&M characters, etc.), but people now deem them as too obvious. Personification now tends to deviate from expectation in regard to style. For instance, an ad for Plus lotion depicts the bottle of lotion drinking a glass of water from a straw. There’s a puzzle to figure out; the personification is more complex. The authors of this article conducted a study in which 187 undergrads looked at ads for lotion from Plus, fruit-and-nut-bars from Mills, snack mix from Landers, and bleach from Excel. “Each participant saw only one version from any given ad set, but saw one ad for each of the four brands” (126). One ad featured personification, one did not, and the two others functioned as controls.

The hypotheses were as follows:

H1: Photorealistic pictures in an ad that show a product engaged in human behavior (i.e., a visual metaphor of personification) can trigger anthropomorphism in the absence of a verbal cue and without use of an animated character.

[…]

H2: Brands featured in ads that use personification will elicit (a) more attributions of brand personality, and (b) more emotional response than brands featured in ads that do not use personification.

[…]

H3: Brands featured in ads with personification will be liked more than brands featured in ads with no personification.

[…]

H4: The impact of personification metaphors on brand attitude, relative to nonpersonification metaphors, is mediated by the impact of personification on emotional response and brand personality attributions. (123-124)

In this study, ads with personification were seen as more effective than those that relied simply on (non-personified) metaphors.

Delbaere earned a Ph.D. in business; McQuarrie is a marketing professor; and Phillips teaches branding and advertising courses. Their experiences in business boosts their ethos in addressing how advertisements affect consumer activity.

On that note, I’ve noticed a clear trend between my research on anthropomorphism – for this class, for English 706, and for my thesis: Research on the effects of anthropomorphism and personification focuses heavily on advertising. Perhaps this i because ads are readily tangible for obvious reasons. However, the literature used in and concepts of this research are useful to my research on smileys, emojis, emoticons… the names often seem to be interchangeable.

Due Monday, Mar. 16

Lebduska, L. (2012). Emoji, Emoji, What for Art Thou? Harlot, 12.

The whole article appears on one page, hence the lack of page numbers in the reference above and in the in-text citations.

Lebduska looks at the history of the emoji, and argues that emojis are not a threat to traditional alphabetic literacy. Instead, they are a creative way to express ourselves; they even clarify tone or content in traditional alphabetic writing, sometimes. Emojis are culturally and contextually bound, and stretch linguistic conditions, as “writing […] always have a visual component mediated by a material world.” In 1982, Carnegie Mellon researchers gave birth to the emoticon – they used the now-iconic : ) (which WordPress automatically makes into 🙂 ) to indicate that the mentioned cutting of an elevator cable was simply a dose of dark humor. Emojis, originally created to boost teenage market share for mobile phone company DoCoMo, emerged almost 10 years later in Japan. They offered a wide array of activities, events, and objects, as well as more fleshed-out compositions than emoticons. They later became part of all web and mobile services in Japan. Google and Apple brought them to the Unicode Consortium in the mid-2000s; 722 codes for emoji were standardized in 2010. Emojis’ capabilities for more efficient communication have come under attack from some, but their meanings are more readily decipherable than, say, cuneiform or approaches from Sir Isaac Pitman and Gregg. However, only those with access to emojis can use them; it would be incorrect to claim universality. Additionally, they cannot act as universal because they represent white “as a universal, non-raced race.” Still, emojis offer people (with access) the ability to buffer confusion often seen in digital communication. They also offer the ability to obfuscate meaning, in regard to “unplain language,” sarcasm, and irony. There are arguments that emojis in themselves are not as heartfelt or genuine as textual messages. However, this regards textual messages as inherently heartfelt and genuine, as if someone cannot be shallow or unauthentic when composing through linguistic means. Lebduska concludes that emojis have just as much potential as words, and offer rich possibilities for the teaching of communication.

Lebduska teaches writing, and it’s refreshing to see an open attitude toward emojis, toward incorporating them into communication curriculum. As the approach taken in this article places specific importance on emoji-inclusive communication, it’s greatly inspired my project. While I knew that my work would be of importance – not only to this class and to my thesis, but also to communication in general – Lebduska’s scholarship connects resources from the past and present to set up a context for why this work is important.

Due Sunday, Mar. 22

Porter, J.E. (2009). Recovering Delivery for Visual Rhetoric. Computers and Composition, 26, 207-224.

Porter hopes “to resuscitate and remediate the rhetorical canon of delivery” (207). The perceived exclusivity of delivery to verbal communication contributed to its rarity in communication, English, and writing courses. He positions delivery as a techne, to give a broader picture of delivery, and proposes that digital delivery consists of the following five components:

- Body and identity

- Distribution and circulation

- Access and accessibility

- Interaction

- Economics

Body and identity refer to online representations and performances of identity; they include gesture, voice, and dress (body), as well as sexual orientation, race, and class (identity). Our representations of ourselves online contribute to our ethos. Virtual spaces can recover visual and speaking bodies, and offer capabilities that duplicate those of the physical world. Distribution and circulation involve technological publishing options. Distribution refers to your packaging of a message to achieve a desired effect; circulation refers to how messages may be re-distributed without your direct intervention and have lives of their own. Access and accessibility involve audiences’ connectedness to Internet-based information. Access refers to how connected a particular group can be, while accessibility refers to how connected a particular group is. As it stands now, many in the general public do not have access to information distributed through digital means. We must try to reduce that gap. Interaction regards how digital designs allow and encourage people to engage with interfaces and with each other. While access is certainly important, engaging with people is crucial, too. Economics often involves legalities like copyright, fair use, and authorship. For instance, digital spaces offer capabilities that challenge industries built through nondigital means (e.g., the Napster brouhaha). Additionally, there’s plagiarism, which is easier now since the digital world makes sharing, and consequently stealing, rather easy. Porter concludes in saying that he hopes to develop rhetoric theory that is useful for the digital age.

Porter’s background in composition and rhetoric gives him major credibility when it comes to addressing contemporary rhetorical issues. As for my own research, emojis are perhaps most relevant to the body/identity component of digital delivery. In his discussion of bodies/identities, Porter discusses the simple : ) emoticon and avatars in Second Life. As Lebduska’s work pointed out, they are more complex than emoticons, but they are certainly not as complex as Second Life avatars – emojis won’t crash your computer, unless you did need to install that software update after all. This particular component of Porter’s work will be relevant to my report here – and likely my thesis, too!

Due Sunday, Mar. 29

Garrison, A., Remley, D., Thomas, P., & Wierszewski, E. (2011). Conventional Faces: Emoticons in Instant Messaging Discourse. Computers and Composition, 28, 112-125.

Garrison, et al. attempted to look at emoticons as their own conventions in IM (Instant Messaging) discourse. Typographic symbols contribute to the composition of emoticons, which have criticized in a broad number of fields. Mainstream preferences lean toward traditional spoken or written discourse, and adhere to the theory that language alone conveys meaning. Garrison, et al. use IM for personal and professional communication, and hope to discover conventions of emoticons in IM. “Due to the reliance on the speech/writing dichotomy,scholarship has been quick to label anything other than familiar forms of print-linguistic text as additive or ‘paralinguistic,’ thereby limiting the understanding of emoticons while not fully accounting for all their potential uses in IM discourse” (114). For instance, the first noted use of emoticons – again, a Carnegie Mellon professor in 1982 – was explicitly paralinguistic. However, people do not always or even necessarily use emoticons for paralinguistic purposes.

In this study, Garrison, et al. looked not at audience perception or the intent of the used language. Rather, they explored the features of language, hoping to look at “the new forms of language within the discourse” (115). They “analyzed an intact data set collected in 2005 by Christina Haas and Pamela Takayoshi for their study of language features of IM. This corpus of data included 59 transcripts of naturally occurring IM sessions, consisting of approximately 32,000 words produced by 108 interlocutors” (116).

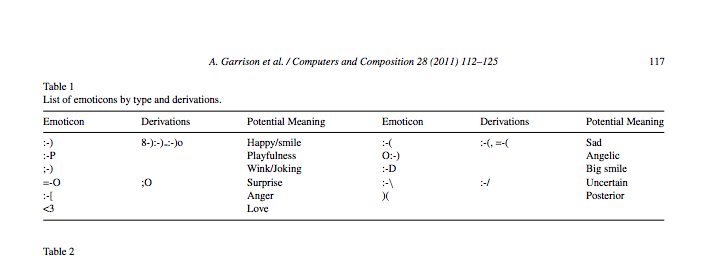

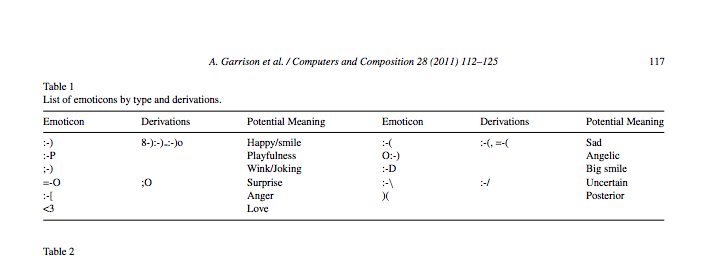

Garrison, et al. coded by derivations based on the mouths of emoticons, as they are important in the user dynamic of American IM. I’ve included the following screenshot that refers to which emoticons they explored, as WordPress automatically changes emoticons to smileys/emojis:

They additionally coded for placement – preceding, within, or following the textual component of the individual message. They also added context to the coding scheme.

Of the 59 IM transcripts explored, Garrison, et al. found 301 different uses of emoticons. The most used emoticons were (loosely translated) : ), : P, and ; ). Interestingly, in regard to placement, emoticons appeared at the end of a line alongside or in lieu of punctuation almost 50% of the time. Ultimately, Garrison, et al. found that emoticons are conventional and inventional, enhance punctuation; they recognize “that standards and conventions arise out of contextualized practices of CMC discourse” (124). Also, we have a more accurate interpretation of emoticons by understanding them as their own semiotic entities.

Garrison, et al. come from English departments. This bolsters their credibility when it comes to communication about, well, communication. The bit about emoticons acting as punctuation is particularly interesting, as I’ve seen at least one other article discussing images-as-punctuation. I wish I had come across this article before making my survey questions.