Fig. 1 Here we see Gay Cat as he appears in his original form.

Introduction

ATRL is a forum-based website for pop-music and pop-culture obsessives that began as a fan site for MTV’s now-defunct music-video-countdown show, TRL (hence its name, which is an abbreviation for “Absolute Total Request Live”). Members of the ATRL community make extensive use of small visual compositions called smileys in their forum posts. These figures, similar to emojis in form, represent a variety of characteristics and moods that might not be easily conveyed in textual form – or could be but are less entertaining and poignant when expressed through linguistic means. (You can find the original forms of ATRL’s smileys and their codes here.)

The use of visual compositions like emoticons, emojis, and smileys in textual communication has led to a persistent uproar among scholars and the popular press about degrading language standards (Baron and Ling, 2011, p. 48; Garrison, et al., 2011, p. 113). However, emojis stretch linguistic traditions and “[open] a gateway to a non-discursive language of new possibility” (Lebduska, 2014). A specific smiley on ATRL called Gay Cat proves this point, and with this project, I ask, how do members of the ATRL community use Gay Cat? Though the smiley makes use of stereotypical visual cues of gayness and queerness, I argue that Gay Cat allows for those in the ATRL community to subvert negative connotations with queer identification as an asset and not as a deficit or as a neutral identification, and to claim, manipulate, and subvert queer identities.

The Significance and Purpose of This Study

Gay Cat is a personified figure who most readily represents the subaltern group of gay, hence the name. The cat, like most other smileys, loosely resembles a well-crafted hand drawing. The personification of this figure is interesting – save for a pair of black kink boots, the cat wears nothing; he smiles and keeps its gaze on you mid-strut. As if the visual signifiers weren’t enough, “Gay Cat” appears in a box of text if you bring your cursor over the smiley.

The incorporation of smileys, emoticons, and emojis into textual communication rubs some academics and some in the popular press the wrong way. For instance, Anthony Garrison, et al. (2011) point to research from Robert R. Provine, et al. (2007) on emoticons, which suggests that they are colloquial but regards them as “an unnecessary and unwelcome intrusion into well-crafted text” (p. 305). However, disregarding their potential as electronically mediated colloquialisms also disregards how subcultures and the subalterns therein may use emoticons, smileys, and emojis. This is important, as queer people, specifically youths, do not have the same opportunities for self-expression as their heterosexual, or non-queer, peers. The ATRL community is understood as heavily comprising of gay youth and young adults, which is perhaps unsurprising – the website is for pop-music and pop-culture obsessives, after all. The following quote, which has appeared in the signatures of several in the community, highlights as much:

This forum is mostly young gay men, struggling to find their place in this world, who finally find an online community where people from around the world share similar interests with them […]. You don’t know someone’s story or how many friends they have (or don’t have) in real life. A bit of social interaction online about celebrities and pop stars might really cheer them up and mean the world to them.

Existing literature in queer theory that regards (queer) representation in digital places emphasizes people’s literal expression of sexuality and sexual desire. Of course, such studies are important, since queer people are marginalized for their expressions of sexuality and gender, which are often regarded as the same despite being different (Richardson, 2007, p. 458). But scholarship should also explore queer representations that exist outside of actual sexual activity, or at least those that do not necessitate sexual activity. What good are queer studies, which seek to resist binaries and, more specifically, rigidly defined categories of sexual and gender expression, if they explore only artifacts that are innately sexual? Since the smiley in its original state exists outside of the heterosexual matrix proposed by Judith Butler (1999), this perhaps makes the use of the smiley alongside rhetoric related to sexual behaviors (double entendres, etc.) even more interesting. Gay Cat allows for and encourages gay and, more broadly, queer representation and interaction as an asset, not a deficit, and can exist outside of literal sexual expression; the smiley allows for those in the ATRL community (regardless of their real-life sexual orientation or gender identity) to enact queer identities and subversion in a place that is not directly associated with sexuality.

![]()

Fig. 2 An emoji approved of by the Unicode Consortium

In form, smileys very much resemble emojis often seen in electronically mediated communication, like the one depicted in Figure 2 above. According to Lisa Lebduska (2014), emojis emerged in the 1990s as “more fleshed-out versions of emoticons […], as well as a pantheon of objects, activities, and events ranging from cactuses to cash” (n.p.). However, emojis and smileys are not interchangeable terms: Emojis are Unicode characters, or approved as “a universal character set for all text, not just English text” by the Unicode Consortium (Mukerjee, 2015, n.p.); smileys are visual compositions that exist outside of Unicode Consortium approval in specific digitial places, like forums.

As ATRL devotes its attention to pop culture – and more specifically pop music – and makes use of smileys in lieu of the emojis seen as standard in mainstream electronically mediated communication, we can understand the website as being the home of a discourse community. James E. Porter (1986) defines the discourse community as “a group of individuals bound by a common interest who communicate through approved channels and whose discourse is regulated” (p. 38-39). More specifically, John Swales (1990) agrees on common goals for the public; “has mechanisms of communication among its members”; works toward information and feedback; uses one or more genres; has acquired a specific lexis; and places a limit on the number of people allowed (p. 23-25). Through this definition, ATRL can be understood as the home of a discourse community, because members share information about music and pop culture with others through linguistic and visual means, make use of “online colloquialisms,” and only open up membership at specific times and will ban people for straying from the conventions placed before them.

Understanding Semiotics and Queer Theory

The Semiotics of It All

The combination of linguistic and visual methods of communication make ATRL an interesting place for exploration of semiotics. Anne Wysocki (2001) argues that we should look at content and form working together, not as separate entities (p. 210). In other words, the visual should not be seen as lesser than or separate from the textual – and vice versa. More specifically, the computer can be understood as a rhetorical device that necessitates exploring the reciprocal relationship between text and image – and more, such as audio, in some cases. To that end, Mary Hocks (2003) defines the (computer) screen as “a tablet that combines words, interfaces, icons, and pictures that invoke other modalities like touch and sound” (p. 631). She points out that new media and their visual and interactive nature amplify the importance of visual rhetoric. “Interactive digital texts can blend words and visuals, talk and text, and authors and audiences in ways that are recognizably postmodern” (p. 629-630).

Semiotician Roland Barthes (1977) suggests that images have three messages: the linguistic message; the denoted image, or literal message; and the connoted image, or symbolic message. The linguistic message tends to either anchor or relay (Barthes, 1977, p. 155-156). Anchoring text appears with advertisements and photographs as a way to contextualize the image(s); relaying text showcases a complementary relationship between image and text (Barthes, 1977, p. 157). Meanwhile, the denoted image (denotation) acts as the start of the study, as the process of making meaning takes place in the connoted image (connotation), which engages those who interpret meaning (Moriarty, 2005, p. 231). In his discussion of the denoted image, Barthes (1977) suggests that “[t]he more technology develops the diffusion of information (and notably of images), the more it provides the means of masking the constructed meaning under the appearance of the given meaning” (p. 159-160). Meanwhile, “connotation reflects cultural meanings, mythologies, and ideologies” in the work of Barthes (Moriarty, 2005, p. 231). All three messages proposed by Barthes should be understood as intertwined and building off one another, not as three separate messages. As forums (like ATRL) see community members incorporating the visual into their textual communication, forums (like ATRL) make use of the linguistic, denoted, and connoted messages proposed by Barthes.

In relationships where the textual affects the meanings of the visual and vice versa, the importance of the visual cannot be underestimated. As it so happens, text relays more often than it anchors in the context of communication seen in electronically mediated communication – in general and in regard to forum websites like ATRL. For instance, Naomi S. Baron and Rich Ling (2011) conducted research on the use of smileys as punctuation in electronically mediated (mostly textual) communication. In addition to discovering that gender was a clear factor, they also found that people often use emoticons to convey emotion (p. 54). While research shows that we can find meaning in electronically mediated communication that strays from text-as-text-alone conventions, it must be complicated to understand how Gay Cat functions on ATRL.

Emoticons are different from smileys and emojis. With emoticons, typographical figures work toward a more readily visual meaning than when they fit into text-as-text-alone conventions, but they are still understood as textual. The construction of smileys and emojis is so far removed from text (digital coding is involved but hidden from the denoted image) that, on a surface level, we do not interpret these compositions as textual, even when used in/alongside textual communication. For this reason, the rhetorical implications of emoticon use and smiley use are different. Likewise, the knowledge of discourse communities showcases that the use of smileys bears different rhetorical implications than the use of (Unicode Consortium-approved) emojis. Additionally, the rhetorical features of interactive digital media can help us understand visual rhetoric. As interactive digital media open up rhetorical possibilities, it allows more groups – like subcultures and subalterns – to speak.

Queer Theory, Queer Subversion, and Queer Rhetoric

R. Mills (2006) proposes that academic historians should engage in a critical dialogue with LGBT history to give it a sense of purpose, “to have a role in shaping and transforming” it (p. 255). LGBT public cultures often adopt coming-out narratives and, similarly, the repressive hypothesis – which suggests that Western homophobia suddenly began to unravel in the 1960s (p. 255). Also, “queer” discourse often marginalizes transgender narratives and people, as well as intersections with race and class (p. 256). Mills suggests that identities make clear distinctions “between gender identity (desire to be) and sexual orientation (desire for)” (p. 257). John C. Hawley (2001) proposes that a queer postcolonialism, which recognizes subalterns within the queer establishment, might be the best way to examine these subalterns’ abilities to speak (p. 5). Additionally, Mills suggests that focusing on identity as a strategy may solve problems within queer discourse (p. 261). James E. Porter (2009) points out that online places allow members of communities to construct their own bodies and identities, which may or may not reflect their nondigital selves (p. 212). Body includes gesture, voice, and dress; identity includes sexual orientation, race, and class (p. 208). Our self-representations in online places contribute to our ethos (p. 212). As ATRL allows all community members to use Gay Cat (and other smileys) in their forum posts, members can construct temporary identities; even though they may not be queer themselves, they have the ability to engage in queer discourse.

Additionally, focusing on identity as a strategy is perhaps the essence of queer theory. Riki Wilchins (2004) highlights research from J. Butler, who suggests that we should subvert identities and question their creation, political ends, erasures, and presentations. Brett Farmer’s (2005) “fabulous sublimity of gay diva worship” serves as a way to use identity as a strategy. In accounting for his own childhood experiences of engaging in gay diva worship of Julie Andrews, Farmer recognizes that mobilization of women stars as vehicles for queer transcendence functions as a practice of “queer sublimity: the transcendence of a limiting heteronormative materiality and the sublime reconstruction, at least in fantasy, of a more capacious, kinder, queerer world” (Farmer, 2005, p. 170). The hysterical excess of the depicted diva worship transcends “the constraints of sexual, social, and textual normativity” and temporarily opens space in which homosexuals can thrive (Farmer, 2005, p. 180). Daniel Harris (1997) points out that the ostracism and insecurities many homosexuals face is at the core of gay diva worship rather than the actual diva (p. 10). Members of the ATRL community enact the practice of (gay) diva worship with (and without) Gay Cat. Even if some community members do not identify as queer and do not challenge the heterosexual matrix in their nondigital lives, their use of Gay Cat challenges their own adherence to the heterosexual matrix, and acts as a legitimate method of praising a music artist.

Blake Paxton builds from Farmer and places the same concepts in a contemporary context that is more relevant to community members’ use of Gay Cat. Basing much of his work on Farmer, Blake Paxton shows how such transcendence can work toward political means, addressing drag performance as a space of gay escape (p. 29). Spaces of performativity threaten the status quo; identity can change in our everyday “performances” (p. 29). Diva performance encourages us to thrive in and enjoy these uncertain spaces (p. 29), disrupts the heterosexual matrix proposed by J. Butler, which reveals that gender itself is a performance (p. 41). Paxton finds that gay men often use diva performance as a way to express their desires when they cannot openly express such desires (p. 41-42). Gay men additionally use diva performance for therapy and connect close relationships they have with women in their lives (p. 76-84). Also, Paxton mentions several instances in which he and other gay men referred to each other as women (i.e. “Hey, girl, hey.”) as a method of camaraderie, not as a way to denigrate each other (p. 92). This ties again into the idea of people carrying out performances that disrupt the heterosexual matrix, performances that can be seen on ATRL in the textual and the visual.

We also see such rhetoric of subversion in Paris is Burning (1990), the classic documentary that centers on New York City’s ball culture that comprises of African-American and Latino gay and transgender people. While not wholly scholarly, the film provides an in-depth look at queer culture relevant to this study. Throughout the film, queer people strut in ball competitions dressed as women and dressed as men; when they are dressed as women, they often wear spiked-heel boots and shoes. The film also features queer people dancing in a style called vogue, which originated in ball culture. The pushback against the heterosexual matrix and the style of vogue are important to a particular exploration of Gay Cat’s use on ATRL.

Exploring Gay Cat

The preceding discussions of semiotics and queer rhetoric work to frame the use of Gay Cat on ATRL. Though simple in visual construction, Gay Cat is a fascinating smiley for exploration in regard to the implications therein. Going by Barthes’ denoted image, the smiley is simply a smiling, cream-colored, anthropomorphized cat with kink boots. However, when exploring the connotations therein, both exciting and problematic components come to light. First, Gay Cat’s “standard” form is white, similar to the emojis in the Unicode Consortium. While Gay Cat’s queerness sets him apart from the status quo, he still fits into the mainstream in regard to race and (seemingly) ethnicity.

Still, we can understand the smiley as performing body rhetoric, which involves how we use our bodies for rhetorical purposes. I see at least four factors that play into his body rhetoric: the oppositional gaze proposed by b. hooks (1992), his nakedness, his strut, and his spiked-heel boots. Gay Cat’s eyes face us; his stare may indicate more than simply what we see. I argue that Gay Cat stares at us, that he employs the oppositional gaze proposed by hooks, which allows black women to critically explore “white womanhood as [the] object of phallocentric gaze,” to deconstruct binaries that divide women and men (p. 122). The general connotations of this concept, such as the deconstruction of absence, can also be applied to queer subversions. The smiley not only looks at us; he stares at us in opposition to our ignorance as a way to negotiate power, to find himself among the deconstruction. Next, Gay Cat’s smile indicates happiness, but we must also understand the smile as a rhetorical act. I argue that this happiness comes from the aforementioned oppositional gaze. He knows that he unsettles us; readily identified as gay through the text, the smiley bears no shame in his sexual orientation. Gay Cat’s nakedness can also be seen as an enactment of body rhetoric. B. Lunceford (2012) points to Western taboos to the naked body (p. ix), which can frame the smiley’s nakedness as a further opposition to the norm. The kink boots that Gay Cat wears also signify a lack of sexual shame. In short, while his whiteness situates him into mainstream society, Gay Cat’s other signifiers proudly announce his queerness.

Methods

I will look at four specific uses of Gay Cat on ATRL that represent four different contexts, because these contexts best showcase the different ways in which members of the ATRL community utilize Gay Cat. While each context depicted sees the smiley acting as punctuation, each works toward different (digitally) visually rhetorical meanings. I have limited my exploration of Gay Cat use on ATRL, both to limit the scope of the overall project and to fit the appropriate conventions (i.e., understood word/page length); additionally, this seems to be the primary (if not the only) place in which people use the smiley. The first use sees Gay Cat functioning alongside a mainstream(ed) use of queer terminology; the second use sees the smiley being used as an act of superiority; the third use sees the uses of Gay Cat in a series of posts that bring forth innuendos and double entendres; and the fourth use sees the smiley appearing in clothing traditionally regarded as women’s clothing.

Uses of Gay Cat on ATRL

Fig. 3 A member of the ATRL community grooves to the music with Gay Cat.

Come On, “Vogue”!

The first use of Gay Cat sees a member of the ATRL community using Gay Cat at the end of a piece of text. This post appears in a forum thread about Rihanna’s live cover of the Madonna song “Vogue,” and quotes the first three words from the song’s chorus. The song’s title derives from a dance often performed in (queer) ball culture and depicted in the aforementioned Paris is Burning; the song also describes this dance as a form of escape. It’s no secret that Madonna has come under fire for cultural appropriation throughout her career (hooks, 1992). While the popularity of the song and its iconic music video did shed a light on queer ball culture, “Vogue” has also functioned as a capitalist gain for the Queen of Pop, and people can enjoy the song without acknowledging or even knowing of the style of dance. While the art of queer people was seen and appreciated, it was only done so through a heterosexual lens. While Gay Cat appears in the form of play, its presence here forces us to connect the song back to the style of dance that inspired it in the first place. Through this use of punctuation, Gay Cat returns to the art of vogueing to its original context.

Fig. 4 A member of the ATRL community implies that maybe Lorde is a royal, after all.

I Wanna See the Receipts

The second use of Gay Cat sees a member of the ATRL community using Gay Cat as punctuation alongside text suggesting that alternative-pop artist Lorde gets her own “receipts” thread. Online communities often use the word “receipts” in the place of “evidence” or “proof” – “Show me the receipts” means “Show me the evidence,” for instance. More specifically, on ATRL, receipts threads function as places to look up certain artists’ music chart histories, concert tour grosses, and music awards, as well as additional accomplishments if said artist is a hyphenate. The use of Gay Cat here connects the textual content to the practice of gay diva worship. This forum post becomes particularly interesting when looking at the “form” that seemingly houses the “content.” According to Wysocki’s work, we must look at these as functioning together; this is perhaps more obvious here than in any other instance described in this project. Given the community member’s avatar (a picture of Lorde) and signature (whose first textual component reads as “Lorde”), we can understand this forum post as coming from a community member who enjoys the music of Lorde. The denoted connotation here seems to be Gay Cat as punctuation for “Let’s do this.” Through this use of punctuation, Gay Cat enacts gay diva worship to symbolize the superiority of a specific music artist.

Fig. 5 A member of the ATRL community discusses croissants and Gay Cat.

Croissant or “Croissant”?

The third use of Gay Cat involves multiple uses of the smiley across forum posts in the same thread that bring forth innuendos and double entendres. An exploration of this continual use of Gay Cat perhaps best explores how members of the ATRL community use the smiley to engage in conversations with each other rather than simply make statements. In a thread dedicated to the adult album alternative artist Adele, members of the community inquire about a community member’s vacation. As Figure 5 above shows, the member used Gay Cat twice in the post. The first use of the smiley can be seen as punctuating the first statement; the two uses of the smiley can also be understood as housing the statement “I had like a total of 5 croissants on the cruise.” The smiley’s repeated use in this particular post can be understood as a regular communal use of the smiley. However, the smileys’ housing of the second linguistic statement also work toward contextualizing the statement toward a double entendre, with croissant referring to what is often seen as the primary male sex organ. The use of Gay Cat in lieu of another smiley is important; the smiley is both gay and male, which contextualizes the double entendre.

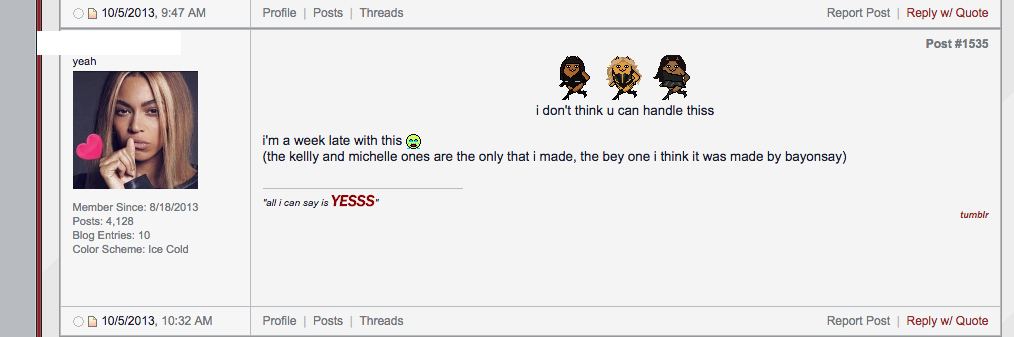

Fig. 6 A member of the ATRL community manipulates Gay Cat to resemble pop group Destiny’s Child.

Gender… Bending?

This fourth use of Gay Cat involves users’ altering of the visual presentation of the smiley. This alteration does not obscure members of the ATRL community from knowing that they are looking at Gay Cat. However, the changes to the visual construction of the smiley offer different rhetorical implications than before. In this particular example, as Figure 6 above shows, a member of the ATRL community places Gay Cat into the post three times. While each instance is visually different, each offers a noticeably darker complexion of skin than the “standard” Gay Cat; the hair and attire also code these manipulations as female rather than male… if we are adhering to traditional gender binaries. The text underneath, which reads, “I don’t think u can handle thiss,” refers to Destiny’s Child’s “Bootylicious,” and would seem to support the notion that these Gay Cats have now “become” the famous woman group through visual manipulation. However, the lack of direct tangible meaning also suggests that Gay Cat in himself may be intact for all three individual uses, and that he is participating in gay diva worship; the member of the ATRL community who composed this post can also be understood as participating in gay diva worship. The obfuscation here renders this particular use of Gay Cat as directly challenging the gender binary more than any other instance referenced here; this particular use of Gay Cat therefore captures the essence of queer theory and forces us to confront gender binaries more than the previous instances.

Conclusion

Content and form work together; the visual and textual cannot be regarded as wholly separate from one another. The Internet exemplifies these concepts, especially in those places that allow people to communicate with each other. ATRL allows members of its community to use smileys, and while it may be easy to overlook a smiley that appears in textual communication or deem it as insignificant, the processes of contextualization and interpretation should never be ignored – especially when subcultures and the subalterns therein are concerned. While Gay Cat fits into the unfortunate white-as-default trope, his proud queerness, and allows members of the ATRL community to represent the enactment of gay and queer practices. Through semiotics and queer theory, we see that community members use the smiley as punctuation in a variety of contexts. All of these contexts show ATRL members using the smiley as a form of play. However, gayness and queerness are never mocked in the form of play; the humor is not malignant but communal. Even if the members of ATRL are not gay or queer themselves, their repeated uses of Gay Cat proudly acknowledge gay and queer identities, rhetoric, and methods of subversion. Gay Cat not only acts as punctuation; he also returns to queer rhetorical practices to their original contexts, suggests the superiority of particular music artists by recalling gay diva worship, allows community members to invoke innuendoes and double entendres, and challenges gender binaries and the heterosexual matrix through clothing.

References

Baron, N.S., & Ling, R. (2011). Necessary Smileys and Useless Periods: Redefining Punctuation in Electronically-Mediated Communication. Visible Language, 45, 45-67.

Barthes, R. (1977). The Rhetoric of the Image. In Handa, C. (ed.), Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook (152-163). New York: Bedford, St. Martin’s.

Farmer, B. (2005). The Fabulous Sublimity of Gay Diva Worship. Camera Obscura, 20, 165-195.

Garrison, A., Remley, D., Thomas, P., & Wierszewski, E. (2011). Conventional Faces: Emoticons in Instant Messaging Discourse. Computers and Composition, 28, 112-125.

Harris, D. (1997). The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture. New York: Hyperion.

Hawley, J.C. (2001). Postcolonial, Queer: Theoretical Intersections. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Hocks, M. (2003). Understanding Visual Rhetoric in Digital Writing Environments. College Composition and Communication, 54, 629-656.

hooks, b. (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation. New York: Routledge.

Lebduska, L. (2014). Emoji, Emoji, What for Art Thou? Harlot, 12, n.p.

Livingston, J. (Producer and Director). (1990). Paris is Burning (Motion Picture). United States: Miramax.

Lunceford, B. (2012). Naked Politics: Nudity, Political Action, and the Rhetoric of the Body. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Mills, R. (2006). Queer is Here? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Histories and Public Culture. History Workshop Journal, 62, 253-263.

Moriarty, S. (2005). Visual Semiotics Theory. In Smith, K., Moriarty, S., Barbatsis, G., & Kenney, K. (eds.). Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media (227-241). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mukerjee, A. (2015). I Can Text You a Pile of Poo, But I Can’t Write My Name. Model View Culture, 18, n.p.

Paxton, B. (2011). My Bad Romance: Exploring the Queer Sublimity of Diva Reception (Thesis). Retrieved from Graduate Theses and Dissertations. (3285)

Porter, J.E. (1986). Intertextuality and the Discourse Community. Rhetoric Review, 5, 34-47.

Porter, J.E. (2009). Recovering Delivery for Visual Rhetoric. Computers and Composition, 26, 207-224.

Provine, R.R., Spencer, R.J., & Mandell, D.L. (2007). Emotional Expression Online: Emoticons Punctuate Website Text Messages. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26, 299-307.

Richardson, D. (2007). Patterned Fluidities: (Re)Imagining the Relationship Between Gender and Sexuality. Sociology, 41, 457-474.

Swale, J. (1990). Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Boston: Cambridge University Press.

Wilchins, R. (2004) Queer Theory, Gender Theory: An Instant Primer. Los Angeles: Alyson Publications.